Django Tutorial: Url Shortner (pt. 1)

I find the starter Django tutorial a bit boring,

so I decided to make my own with a very popular first app: URL Shortener. This tutorial covers Django concepts

like Models, URL Mappings, URL Routers, Views.

What’s a url shortener?

Similar to shorturl.at, we will be able to post any convoluted link and receive a shortcut version of it.

Project Setup

First, we’ll start with creating a python virtual environment. We shouldn’t concern ourselves with what version of python or Django we will be installing as we won’t be using any special features that are available in a specific Django version. All of the tools were available since earlier versions of Django.

mkdir -p ~/github/url_shortener # create our directory

cd ~/github/url_shortener/

git init # start a git project

python3 -m venv venv # start a virtual environment

source venv/bin/activate # enter our virtual environment

pip install Django # installed the latest version of Django

Project Structure

By default, Django provides commands like startproject or startapp. As they run, they

create a lot of non-obvious files/setups for beginners. Let’s not run those and instead

add each file as we go and try to understand what is happening behind the scenes.

manage.py

At the root of every project lies manage.py file. It is autogenerated by the Django setup. Let’s take a closer

look at it. I’ve removed some text to make it more readable.

#!/usr/bin/env python

import os

import sys

def main():

os.environ.setdefault("DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE", "config.settings.dev")

try:

from Django.core.management import execute_from_command_line

except ImportError as exc:

raise ImportError(

"Can't import Django!"

) from exc

execute_from_command_line(sys.argv)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

os.environ.setdefaultchecks if DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE exists in our environment, otherwise it sets the value to a default provided by the second argument of the function.- The most important parts of the code is the attempt to import Django’s

execute_from_command_line. If Django is not available in the environment, the code will fail. - If the import is successful,

execute_from_command_linewill run any arguments passed through thesys.argv

Thus, manage.py provides us with the interface to interact with Django directly. We are able to create database migration files, run migrations and start the dev server. Let’s go ahead and add this manage.py at the root of our project directory.

Creating an app

Django uses the concepts of apps and to start a basic Django server locally we’ll need a folder called app with three files.

├── app

│ ├── settings.py

│ ├── urls.py

│ └── wsgi.py

├── manage.py

Let’s go over every single file before proceeding.

settings.py

As we saw in manage.py source code, it is essential to load Django’s settings module. Django keeps all of its internal configurations

there. By looking through someone’s settings file, we may answer questions like

- Which database is the project using?

- Where do we store static files?

- What apps are currently loaded?

- What templating engine is used?

- Are we using any custom middleware?

You may copy this file into app/settings.py verbatim.

Let’s go over some important defaults we care about for this tutorial.

-

DATABASESsection tells us we’re using an sqlite3 as our database. Django can work with many powerful databases by default, but we can get by with an sqlite3 engine today. -

WSGI_APPLICATIONsection tells us the path to the wsgi setup. More on wsgi in the next section. -

ROOT_URLCONFsection tells us which file will be responsible for routing the urls at the top level. -

INSTALLED_APPSwill contain a list of native Django apps, your own apps and third-party software likedjangorestframeworkwhich you will work for if you want to build a robust API server in Django.

Sections like MIDDLEWARE and TEMPLATES are too advanced for the purpose of this tutorial.

We will let them work as a black box for today.

urls.py

from Django.contrib import admin

from Django.urls import path

urlpatterns = [

path('admin/', admin.site.urls),

]

The urls.py file tells our Django server how to route any request.

If you go to mywebsite.com/abcdef, Django will read the abcdef part and route you to a correct view.

If those routes/pages do not exist, Django will appropriately route you to a 404 page.

wsgi.py

WSGI stands for Web Server Gateway Interface.

If you’re not familiar with wsgi, please refer

to this wikipedia article.

It is a very common way of running

web servers using python. Take a look at the following code and notice that the only

thing is happening is import of the get_wsgi_application and its assignment to the

application variable.

import os

from Django.core.wsgi import get_wsgi_application

os.environ.setdefault('DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE', 'app.settings')

application = get_wsgi_application()

Understanding Django ORM

Now that we have our barebones Django setup, let’s run the server.

Run python3 manage.py runserver and notice that the following happened:

- You have received a warning

You have 18 unapplied migration(s)... - A new file called

db.sqlite3has appeared at the root of your project.

A note on Django ORM. The reason a lot of people choose Django as a backend server is its integration with databases. Django provides very powerful Object-Relational Mapping tools. Sometimes as devs we take a lot of things for granted. Not having to write database schema updates by hand is one of them.

SQLite Browser

Proceed to sqlitebrowser.org and download the latest version of software. If you’re on a mac with brew installed, you may also run

brew install --cask db-browser-for-sqlite

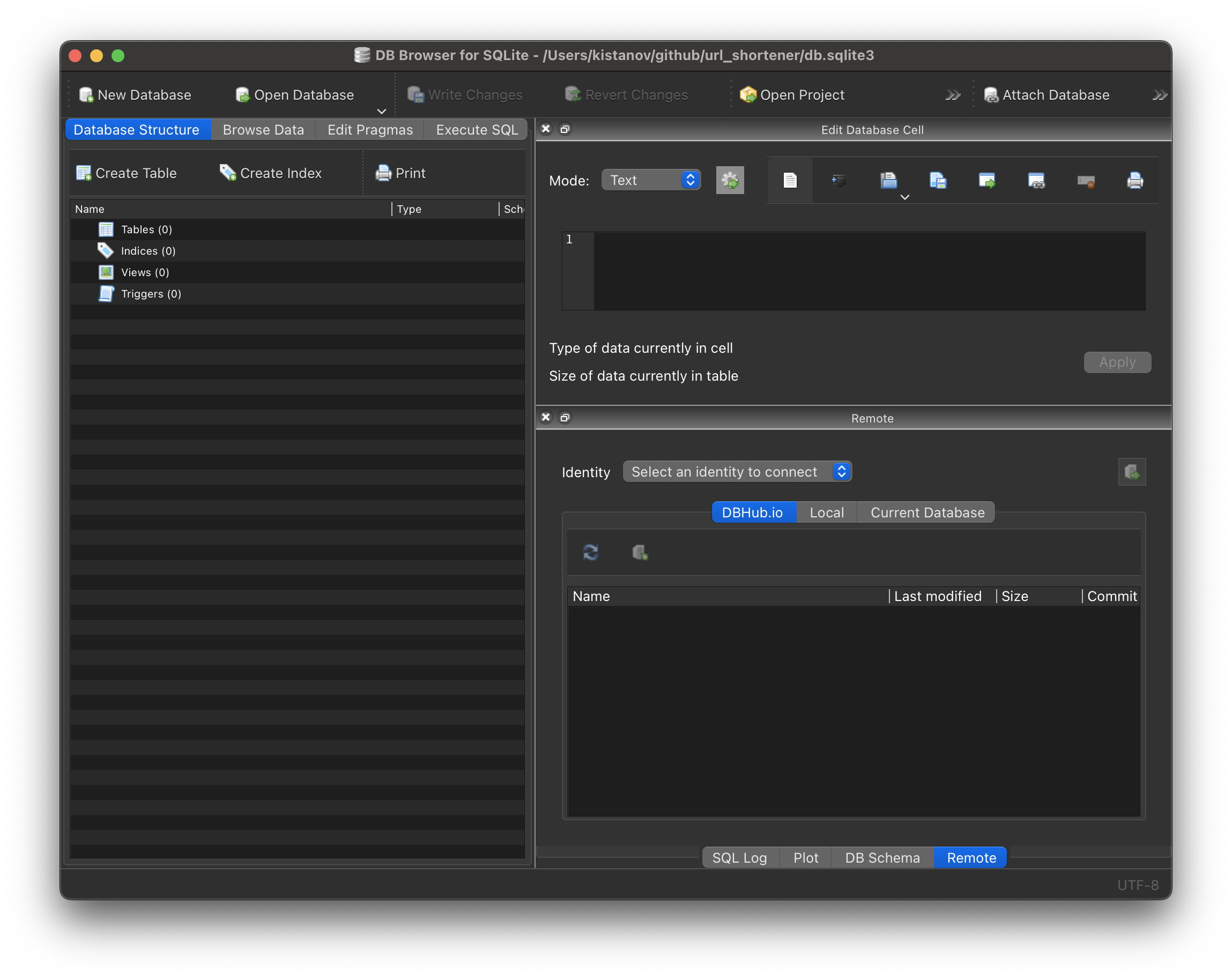

Let’s go ahead and open up our newly created db.sqlite3 inside our repository.

As shown on the picture below, the database is completely empty.

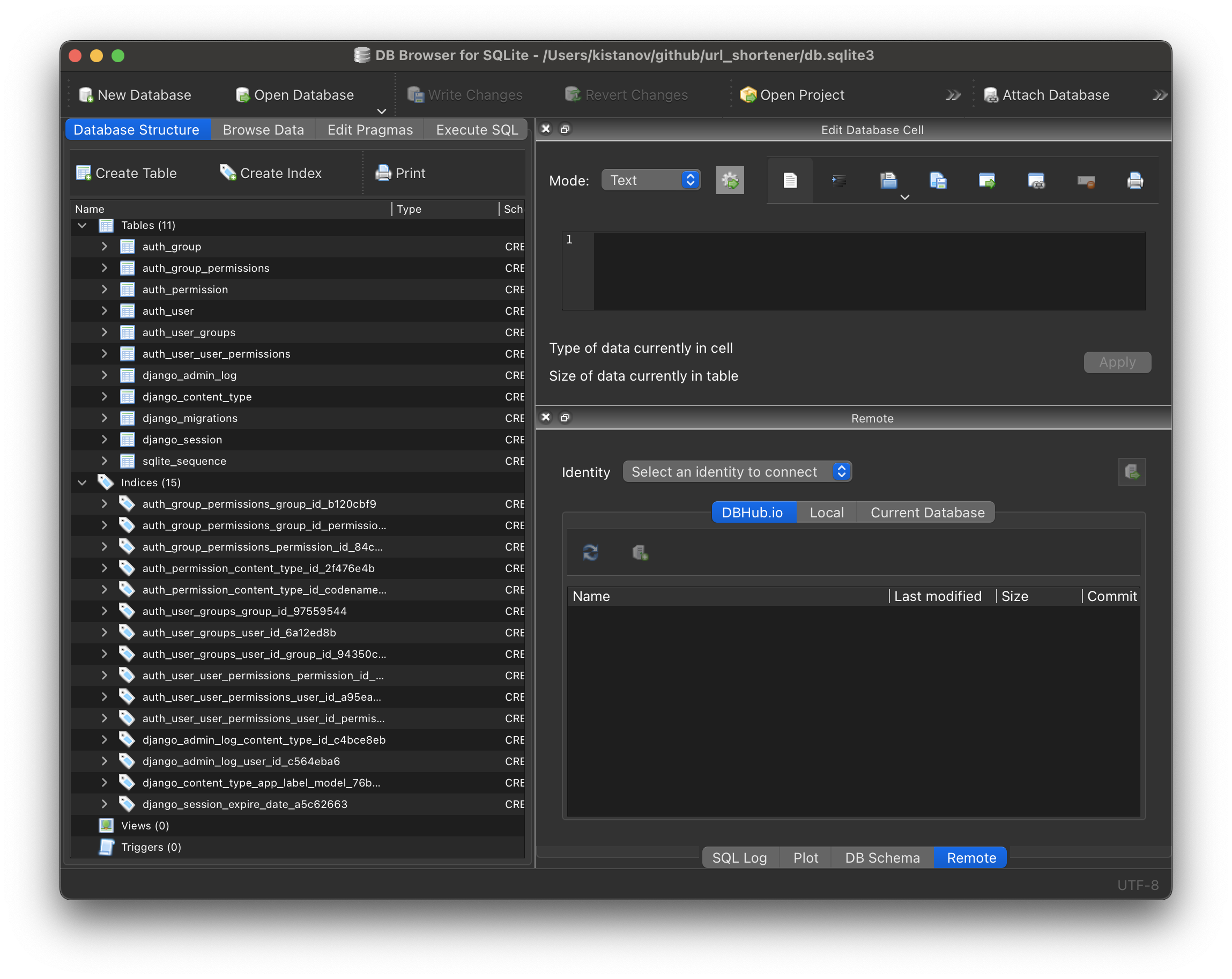

Once we run python3 manage.py migrate, we notice the difference

11 tables and 15 indexes created. So, what is happening under the hood?

- Django starts the server and looks at

INSTALLED_APPS. - For each app, it looks at a table

django_migrationsand ensures all migrations are applied. - For each migration file, Django translates the python code into valid sqlite schema and runs

it on your

db.sqlite3file.